Harrison Mooney on Growing Up Black in B.C.

Really, everything was white, except for the experience of being in my body. I just felt like there’s something people aren’t understanding; that things are different for me. And I wanted to explain that.

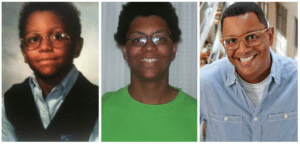

For author Harrison Mooney, the experience was filled with confusion and disconnectedness. He spent his life feeling simultaneously singled out and invisible in a family and church community that fervently ignored his Blackness and dismissed both his encounters with racism and his efforts to articulate his struggles.

For author Harrison Mooney, the experience was filled with confusion and disconnectedness. He spent his life feeling simultaneously singled out and invisible in a family and church community that fervently ignored his Blackness and dismissed both his encounters with racism and his efforts to articulate his struggles.

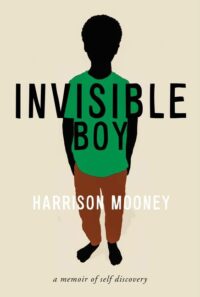

In his powerful memoir, Invisible Boy, Mooney explores the experience of transracial adoption from the perspective of families that are torn apart, and children stripped of their culture, to fill evangelical communities’ demands for babies. It is a deeply personal tale of a Black coming-of-age narrative set in a world with little love for Black culture.

Mooney, who has worked for the Vancouver Sun for a decade as a reporter, editor and columnist, and whose writing has appeared in the National Post, the Guardian, Yahoo and Maclean’s, discussed his book at an in-person and online event at Housing Central on Feb. 16, as part of our month-long celebration of Black History Month.

“The first time I read a book by a Black author I was 21 years old,” Mooney said of The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin. “I remember the feeling of reading that book so vividly because it was the experience of being spoken to.”

But it wasn’t just books where the younger Mooney didn’t see himself or feel a sense of connection to his Black identity. Adopted into a white family in Abbotsford—part of B.C.’s Bible Belt—Mooney was raised in the world of evangelical Christianity that had no place for diversity and little interest in even acknowledging the existence of racism.

Entirely isolated in a seemingly tight-knit community, Mooney spent 20 years searching for a sense of self that remained elusive until stumbled into a graduate American Literature class with reading list that featured a treasure trove of Black authors.

“For the first time in my life, I knew how it felt to have a book speak directly to me,” Mooney writes in his book. It set him on a path of self-discovery and radicalization that crystallized in Invisible Boy, including the realization that the books he wrote as a child and as a teenager may have seemed like fantasy tales about lizards and other strange characters but which were, in reality, his way of making sense of his situation.

“I was clearly writing about a boy completely lost in a country he didn’t understand, whose only wish was to belong,” Mooney recalled. “Really, everything was white, except for the experience of being in my body. I just felt like there’s something people aren’t understanding; that things are different for me. And I wanted to explain that.”

“I wanted to explain to [my parents] that when you’re Black, you need to stay on high alert, you know someone will touch your hair or make an off-colour joke – or an on-colour joke… so you’ve got to stay on high alert.”

They dismissed his concerns, but the power of writing to help Mooney articulate his experiences stayed with him, allowing him to express emotions – sadness, confusion, outrage and frustration – for which he didn’t yet have a voice.

Reading Black authors began to change that, however, and enabled Mooney to see his life through a new lens. “For the first time I saw myself, not as a boy out of time, but as a Black boy placed in a hostile environment and shut out completely from anyone who might share or corroborate his experience, or give him any guidance for how to take control of the experience of having his body.”

He realized he needed to start over, and forge an identity of his own making that stands on the stories, histories, experiences, culture and connection of the Black people who came before him and stand with him today. Invisible Boy is a recounting of that journey and an outstretched hand to anyone who feels isolated and erased so that, like his experience reading Baldwin, others might finally feel seen.

Housing Central reflections on Invisible Boy

Michelle Iverson, CHF BC Chief Operations Officer: We are housing advocates, managers and providers with a goal of a safe, affordable home for everyone. Perhaps today you expand the definition of what safe means for a person of colour. Perhaps you understand the impacts of racial invisibility not just for Black people but any ethnic group and especially a person of colour.

The colour of you follows us wherever we go and I wear mine with pride, but that isn’t always the case for many of the people we interact with. I hope you have a new appreciation for the significance of seeing colour in the spaces people call home.

When we choose to see colour, it means we see the real experiences of others with an understanding that their stories are often muted. It takes work but we can do that work together to respect our difference.

Ed Dagsaan, CHF BC Education Director: This is one of the quotes that stood out to me: “With enough experience, one begins to see oneself, on purpose or otherwise, through other eyes, indifferent, standing off a ways, reacting to the violence like the victim isn’t you.”

To me so much of his story was centred around how he is perceived by others that clouded his own understanding of himself. To us, how do other people’s perceptions feed into our sense of being and belonging? So much of growing up involves crafting one’s own narrative, filtering out all the noise of what one is perceived to be.